A FORSEA Democratic Struggle Series | Essay 1 | Maung Zarni

“My government’s Burma policy is unconscionable. We made empty promises to the Hungarian democrats in 1956. Then when they were slaughtered (by the Soviets), we did nothing. So, you Burmese must find your own solutions”, said Matt Daley, then serving as the Deputy Assistant Secretary of State in the Bureau of East Asian Affairs, at the United States State Department, or foreign ministry.

He was referring to the tragic incident of the Hungarian Uprising of October 1956 during which 30,000 were slaughtered by the Soviet and Hungarian troops. According to the BBC, US President and ex-General Dwight Eisenhower publicly said, “I feel with the Hungarian people” (in revolt) while his Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles, misled the revolutionaries, making a promise which the US was not prepared to keep. In Dulles’ words, “to all those suffering under communist slavery, let us say you can count on us.” In the end, the Americans did nothing for the democrats on the streets of Budapest while the Soviet tanks rolled in to put a bloody end to the uprising.

Daley was a US Army veteran, who only several years before the ill-fated Hungarian Uprising, fought on the Korean peninsula where North Korea, backed by Maoist China and the USSR, fought their US-backed brethren in the South, for 3 years (1950-53). Subsequently, he served as a member of the Secret Service for US presidents and vice presidents, before ending up as a foreign policy official in political affairs at Foggy Bottom.

He saw through the rhetoric of pro-democracy Burma policy, a polemical repeat of US policy towards Hungarian democrats. Unlike many of his American colleagues who had Burma as part of their portfolio, Daley was not going to robotically repeat Washington’s official line towards my country’s affairs.

Instantly, I was very favourably impressed by his candidness.

Having read the old dispatches from Bangkok to Washington, George Kent, the then head of the political affairs at the US Embassy in Bangkok, told me in Thailand – where we were both based around 2010 – about Daley’s past un-orthodox “diplomatic” moves. Kent said that Daley was “a maverick”, who went to see the Karen revolutionaries, without prior authorization from his superiors, during his (Daley’s) time as a political affairs officer in Bangkok.

As a matter of fact, Daley himself told me that he dropped the US Government script about Burma when he met his Chinese counterparts in Beijing and pushed for a more sensible strategic position: he was pushing the Chinese to help persuade the Burmese generals towards a more liberal approach to politics.

I am sure Daley also had other motives, such as US business interests in Southeast Asia, as he became the chair of the US-ASEAN Business Council, after he took an early retirement a year or so after our working together to find Burmese solutions to Burma’s crises. All human behaviours are triggered by a multiplicity of motives, and it is foolish to assign one sole intent to a single conduct.

Whatever his un-stated self- or corporate interests at work, I do not believe that any other interests of his diminished, in any way, the solid fact that he had offered me as a Burmese activist looking for solutions, not being trapped in a single policy paradigm, sanctions or engagement: that the United States was merely talking the talk of rights and democracy but could not be expected to walk its pro-democracy talk.

Daley and I were meeting one-on-one for the first-time in his office at Foggy Bottom, a short walk from George Washington University. We were introduced, via email, by a mutual friend and a long-time Burma watcher, Professor David Steinberg at Georgetown University School of Foreign Affairs. I was portrayed to Daley as “an influential Burmese activist”, who had, through the campus-based Free Burma Coalition, built significant grassroots support for Aung San Suu Kyi’s push for Western sanctions.

In those days, the western world of governments, mass media and civil society networks kissed the ground the Burmese opposition leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, walked on. Her staunch support for maintaining economic and political sanctions against Burma, under a tight grip of her military captors who had put her under house arrest, on-and-off, had established the Burma Orthodoxy in Washington – and other western capitals such as London, Brussels, Ottawa, and so on.

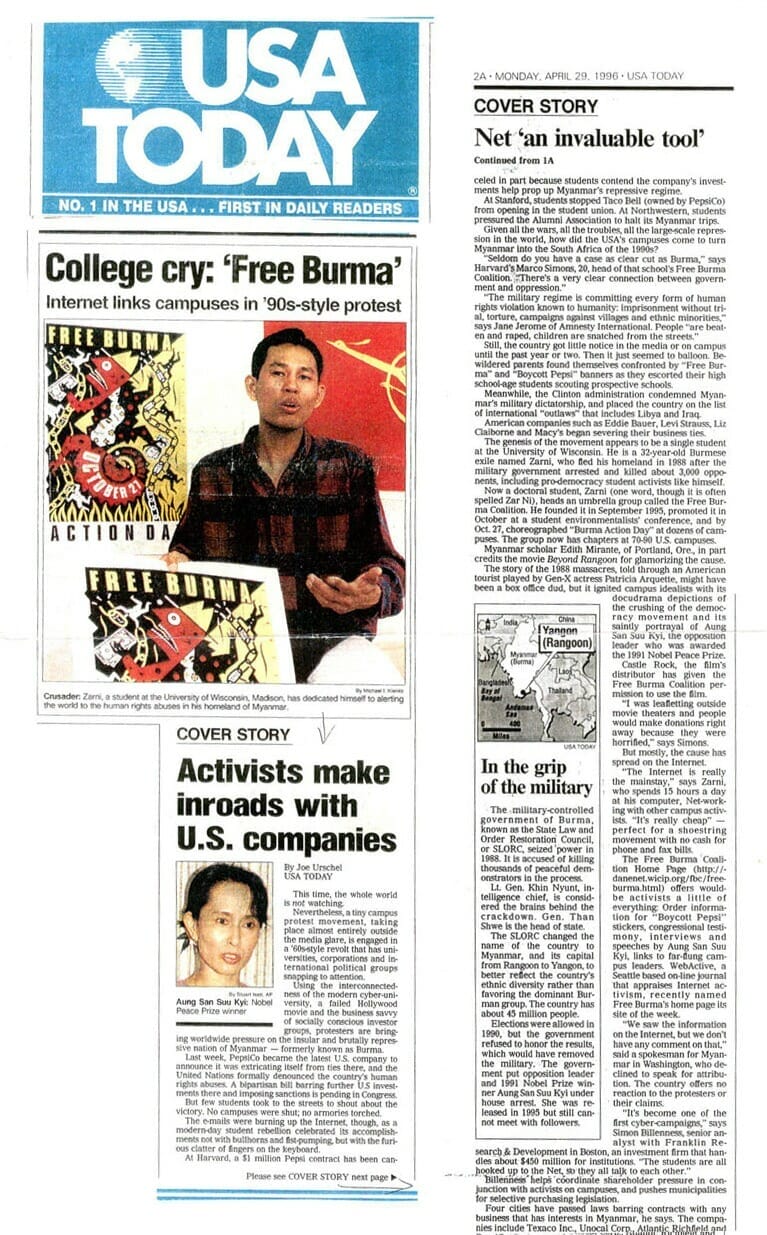

Christian Science Monitor coverage of the Internet and the wave of campus political activism, 31 October 1995

Previously, the United States had embraced the Burmese military dictatorship of General Ne Win who overthrew the democratically elected government of Prime Minister U Nu in March 1962, just as it did anti-Communist strongmen in Africa, Latin America, and Asia during the Cold War. But with the threat, power, and cohesion of the Eastern Bloc visibly on the wane, Washington rediscovered the values of the lives of democrats and activists in far-flung places such as Myanmar, where several thousand unarmed and peaceful protesters were gunned down by the US-supported repressive regime of General Ne Win.

To his credit, the US Ambassador Burton Levin, from Minneapolis, personally witnessed through his glass office window on Merchant Street in Rangoon, security forces machine-gunning down scores of young high school and university student protesters in the months of the 8.8.88 uprisings (8 August 1988) and subsequently succeeded in persuading his government to downgrade US diplomatic ties with Burma, from ambassador to charge d’ affairs, as a token measure of disapproval of the Burmese military leadership’s behaviour.

The US downgrading diplomatic relations in 1989 by the presidential executive order was one thing, but to impose proper economic and other sanctions, required the involvement and support of US Congress. Aung San Suu Kyi’s international influence among policy and media circles had risen dramatically, especially after she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991 – two years after she entered the Burmese opposition movement. And her call for international punitive measures, including economic sanctions, was picked up by grassroots activists globally.

US campus activists and other activist communities took a keen interest in the initially, student-led, pro-democracy uprisings and began exploring different options for concrete offers of transnational solidarity and support for their Burmese peers, who in their minds, were sacrificing their lives and youth as armed revolutionaries under the All-Burma Students Democratic Front, or ABSDF. The American activists, as well as their counterparts in liberal Europe turned to Suu Kyi for policy cues while rediscovering the strategic value of anti-apartheid era consumer boycotts, corporate withdrawal, or divestment and national level economic sanctions.

Thanks to the new-found western media interest in Burma’s affairs, activist campaigns for Burma divestment across USA, Canada and Europe began to gain traction with US politicians, and policymakers in the executive branch. Almost 10-years after the US Ambassador, Burton Levin, called for strong punitive measures against military-ruled Burma, US President, Bill Clinton, signed into law the Burma Democracy and Freedom Act of 2007, with one consequential caveat being that the existing US oil and gas investment, (and any other US business deals), would be exempted from the sanctions. Thanks to the effective lobby by US oil and gas, and other corporate sectors such as heavy-industry equipment exporters, the originally stringent Burma sanctions bill was watered down by the bipartisan team of powerful senators with close ties to the fossil fuel industry, namely, Senators Diane Feinstein of California and William Cohen of Maine.

So, Matt Daley’s blunt words – that the United States could not be counted on as a reliable backer of the ongoing Burmese opposition movement, made up of select ethnic armed resistance organisations, particularly the Karen National Union, and in-country non-violence resistance under the leadership of Ms Suu Kyi and her NLD party – woke me up rudely, and confirmed my suspicion that the sanctions were not the magic bullet.

After all, I had spent a decade, or so, in having invested so much of my labour and time in helping build the pro-sanctions grassroots movement, using the then emerging worldwide web, university-issued emails, and the AOL email services. This was the road to Damascus moment for me, as a staunchly pro-sanctions supporter, of our democratic leader, Suu Kyi.

On the Free Burma campaign, boycott of multinationals profitting from their business with Myanmar/Burma’s military regime.

Early interview with ZARNI, USA, 1996.

Additionally, by 2004, it was becoming quite apparent to me and a small group of overseas Burmese activists who began to see that the US sanctions with its pro-US corporate loopholes, were not doing the job they were meant to: despite US sanctions and our successful grassroots consumer boycott campaigns, especially with investors who were sensitive, or vulnerable to, consumers’ opinions, such as Levi Strauss, Pepsi-Cola, and so forth, the Burmese military regime remained, as intransigent towards any compromise with the democratic opposition, as it was repressive, towards Burmese dissidents.

As long as the substantial flow of revenues from western gas and oil industry – for instance, from Total of France and Chevron of the USA – remained uncut, the Burmese military had more than enough financial wiggle room. As a detour, the pro-sanctions campaign, today remains in this policy advocacy space, calling on the world to turn off this crucial revenue tap for the Burmese military, to no avail.

“Abandoned” by its Cold War-era backers such as the US, the UK, West Germany – by then the unified Germany – and even Japan, the Burmese military had built closer ties with China, of the post-Tiananmen Square crack-down era, and, additionally, allowed itself to be brought into the expanding regional bloc of Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN) exactly the same year the United States imposed its first economic sanctions as a matter of national policy.

However, with the opposition leader with her symbolic monopoly grip on what had been seen as the “Burma sanctions orthodoxy” of the Western governments, blocs (such as the EU), and the media and activist networks that treated any utterances made by Aung San Suu Kyi as if they were biblical, any other Burmese activist exploring policy alternatives, including engaging with her military jailers, was a highly risky affair.

To be continued.

Zarni and student activists from the Free Burma Coalition and the Student Coalition for Corporate Responsibility holding a protest against the university’s investment in Burma-linked US corporations during the University of Wisconsin Board of Regents, Fall 1997.

Maung Zarni